Introduction

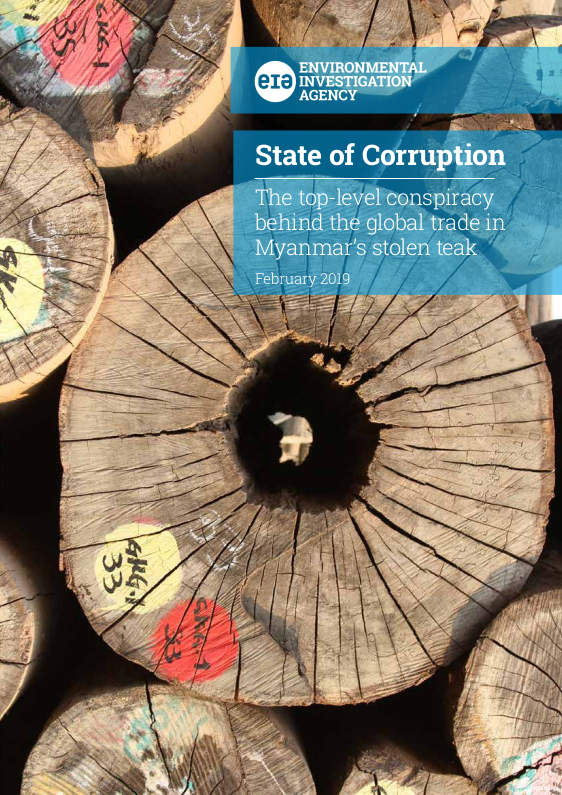

The forests of Myanmar are defined by their monetary value and have been part of the military and economic elites’ profits and, in some cases, survival for decades. The entire legal state forestry and timber trade sectors are riddled with corruption.

Current laws seem to seek the criminalisation of local people and the Government is undermining the communities’ reliance on resources while at the same time introducing a centralised system of management they are unable to implement.

Myanmar’s government presents the teak trade as being wholly legal and sustainable, produced in compliance with the rule of law. This is simply not the case.

A two-year undercover investigation by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) into a near-mythic ‘Burmese teak kingpin’ who conspired with and bribed the most senior military and government officials in Myanmar has revealed how he was able to establish a system of fraudulent trade. This was run in parallel to, and within, the official legal trade administered by the Myanmar Timber Enterprise (MTE) – a state-owned company with a monopoly on all logging and timber trade in the country.

Introduction

The forests of Myanmar are defined by their monetary value and have been part of the military and economic elites’ profits and, in some cases, survival for decades. The entire legal state forestry and timber trade sectors are riddled with corruption.

Current laws seem to seek the criminalisation of local people and the Government is undermining the communities’ reliance on resources while at the same time introducing a centralised system of management they are unable to implement.

Myanmar’s government presents the teak trade as being wholly legal and sustainable, produced in compliance with the rule of law. This is simply not the case.

A two-year undercover investigation by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) into a near-mythic ‘Burmese teak kingpin’ who conspired with and bribed the most senior military and government officials in Myanmar has revealed how he was able to establish a system of fraudulent trade. This was run in parallel to, and within, the official legal trade administered by the Myanmar Timber Enterprise (MTE) – a state-owned company with a monopoly on all logging and timber trade in the country.

Myanmar’s forests

Diverse and extensive, Myanmar’s forests form part of the ‘Indo-Burma Hotspot’, one of the world’s most important biodiversity areas, featuring a huge range of endemic flora and fauna. More than 200 globally threatened species live in Myanmar’s forests, including elephants, tigers, sun bears and the Myanmar snub-nosed monkey.

These forests are an important source of food and fuel for Myanmar’s people, 70 per cent of whom live in rural areas where forests underpin basic livelihoods.

Teak’s combination of properties – a range of beautiful golden-to-red hues on tight, straight grains, Category 1 durability classification, termite, water and insect resistance and its excellent machinability and weathering properties – have earned it the moniker of ‘King of Woods’.

‘Myanmar teak’ or ‘Burma teak’ refers only to wood from Tectona grandis trees growing naturally in Myanmar. Myanmar teak is considered the best true teak available on the planet.

Myanmar’s forests

Diverse and extensive, Myanmar’s forests form part of the ‘Indo-Burma Hotspot’, one of the world’s most important biodiversity areas, featuring a huge range of endemic flora and fauna. More than 200 globally threatened species live in Myanmar’s forests, including elephants, tigers, sun bears and the Myanmar snub-nosed monkey.

These forests are an important source of food and fuel for Myanmar’s people, 70 per cent of whom live in rural areas where forests underpin basic livelihoods.

Teak’s combination of properties – a range of beautiful golden-to-red hues on tight, straight grains, Category 1 durability classification, termite, water and insect resistance and its excellent machinability and weathering properties – have earned it the moniker of ‘King of Woods’.

‘Myanmar teak’ or ‘Burma teak’ refers only to wood from Tectona grandis trees growing naturally in Myanmar. Myanmar teak is considered the best true teak available on the planet.

Deforestation

In recent decades Myanmar has suffered a deforestation crisis.

Timber extraction is considered the main driver of forest degradation inside the country’s forest reserve areas. Overharvesting has been “long term and systematic, persisting until forests are exhausted”. Nominally legal forestry operations by MTE and its subcontractors – which prioritised revenue generation – have not allowed forests to recover between cycles of harvesting. Illegal logging is also a major contributor to forest loss in Myanmar, with EIA investigations in 2014/15 revealing how Myanmar’s military and ethnic armed organisations both profit from the massive illegal timber trade.

Demand for Myanmar teak in Western markets is largely driven by the furniture and boat-building sectors, particularly the yacht and superyacht decking market which seek the highest grades of Myanmar teak. The biggest direct markets for Myanmar teak are China, India and Thailand, which between them imported a staggering 4.04 million m3 of teak logs and sawn timber direct from Myanmar between 2007-17, worth $2.79 billion.

1990s

Myanmar loses 4.3 million hectares of forest

2002-14

Myanmar loses a further 2 million hectares of forest

Since 1990 Myanmar has lost about 20 per cent of its forests

Deforestation

In recent decades Myanmar has suffered a deforestation crisis.

Timber extraction is considered the main driver of forest degradation inside the country’s forest reserve areas. Overharvesting has been “long term and systematic, persisting until forests are exhausted”. Nominally legal forestry operations by MTE and its subcontractors – which prioritised revenue generation – have not allowed forests to recover between cycles of harvesting. Illegal logging is also a major contributor to forest loss in Myanmar, with EIA investigations in 2014/15 revealing how Myanmar’s military and ethnic armed organisations both profit from the massive illegal timber trade.

Demand for Myanmar teak in Western markets is largely driven by the furniture and boat-building sectors, particularly the yacht and superyacht decking market which seek the highest grades of Myanmar teak. The biggest direct markets for Myanmar teak are China, India and Thailand, which between them imported a staggering 4.04 million m3 of teak logs and sawn timber direct from Myanmar between 2007-17, worth $2.79 billion.

1990s

Myanmar loses 4.3 million hectares of forest

2002-14

Myanmar loses a further 2 million hectares of forest

Since 1990 Myanmar has lost about 20 per cent of its forests

Myanmar: A history of Forest Governance Failures

Since the mid-1800s, Myanmar has suffered repeated cycles of excessive and illegal harvesting and timber trade underpinned by corruption, cronyism and conflict.

Myanmar: A history of Forest Governance Failures

Since the mid-1800s, Myanmar has suffered repeated cycles of excessive and illegal harvesting and timber trade underpinned by corruption, cronyism and conflict.

Teak grading in Myanmar

Myanmar teak’s array of qualities mean high grades are significantly more expensive than lower grades.

Under MTE’s grading system, the highest quality logs – for decorative veneers – are Grade A.

Teak logs used for non-veneer applications including furniture, flooring, exterior decking and yacht decking are classified as Saw Grade (SG), with SG1 being the best and SG9 being the lowest grades.

SG1 logs sell for as much as US$5,500, while SG5 logs can sell for less than US$2,000.

MTE’s timber sharing contracts require all logging subcontractors to give MTE all SG1-SG4 teak logs harvested free of charge, to be subsequently sold through MTE auctions. Teak logs of SG5-SG9 can be retained by subcontractors, who pay MTE below-market rates for them and profit by selling at true market prices.

Despite being illegal, and impossible without collusion from MTE or Forest Department staff who grade the logs, misdeclaring SG1-SG4 logs as SG5 or lower has been a common method for subcontractors to increase profits for decades.

Teak grading in Myanmar

Myanmar teak’s array of qualities mean high grades are significantly more expensive than lower grades.

Under MTE’s grading system, the highest quality logs – for decorative veneers – are Grade A.

Teak logs used for non-veneer applications including furniture, flooring, exterior decking and yacht decking are classified as Saw Grade (SG), with SG1 being the best and SG9 being the lowest grades.

SG1 logs sell for as much as US$5,500, while SG5 logs can sell for less than US$2,000.

MTE’s timber sharing contracts require all logging subcontractors to give MTE all SG1-SG4 teak logs harvested free of charge, to be subsequently sold through MTE auctions. Teak logs of SG5-SG9 can be retained by subcontractors, who pay MTE below-market rates for them and profit by selling at true market prices.

Despite being illegal, and impossible without collusion from MTE or Forest Department staff who grade the logs, misdeclaring SG1-SG4 logs as SG5 or lower has been a common method for subcontractors to increase profits for decades.

The Shadow President - King of Burma Teak

In 2016, well-placed sources alluded to the existence of a teak kingpin, allegedly an untouchable and unknowable “ghost” behind Myanmar’s State-administered teak trade.

EIA’s sources suggested his name was “something like” PC Cheng, PC Chang or PC Chun, but could not identify him.

Then, in late 2017, EIA undercover investigators travelled to Taiwan – a centre of world-renowned teak saw millers – and the truth began to emerge.

EIA investigators met with Mr Zheng Kun Fu aka “A-Fu” of Kui Jay Corporation. He said he bought all his logs from a Hong Kong company called Xiangxin (Cheung Hing) said to be headed by a major player, whom he named as “Cheng Pui Chee.”

Cheng Pui Chee sounded exactly like the rumoured teak kingpin PC Cheng.

Cheng Pui Chee

A-Fu alleged that Cheng Pui Chee engaged in high-level corruption in collusion with senior Myanmar officials to defraud the state of timber revenues. Cheng’s corrupt acts allegedly included multi-million dollar bribes, and paying for the foreign education of the children of regime officials for a generation – all in exchange for preferential cut-price access to the best teak.

A-Fu

A-Fu’s claims were corroborated in July 2018 by teak traders working at Yuli Wood, in mainland China, who were acquainted with Cheng Pui Chee, including Mr Zheng Tianren.

Cheng’s corruption reportedly went to the very top of Myanmar’s military administration. While Myanmar did not have a President during the period concerned, A-Fu can only have been referring to the de-facto leader of the country. During the period this corruption allegedly occurred (from the early 1990s to 2014), this can only have been Senior General Than Shwe, the head of the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) and (SPDC) Commander In Chief of the Myanmar Armed Forces from 1992 to 2011.

Through these completely illegal arrangements, Cheng became perhaps the world’s largest teak trader working within the official ‘legal’ system of trade administered by the MTE.

Zheng Tianren

EIA sought to confirm “Cheng Pui Chee’s” full identity, and corroborate the story we had heard.

Cheng reportedly began his career under his father, importing teak into Hong Kong from Myanmar and Indonesia through his company Cheung Hing.

Publicly available sources about Cheung Hing give tantalising hints at connections between Cheng and influential timber cronies close to senior regime officials in Myanmar including Tay Za, who reportedly held shared in Cheng’s Hong Kong firm Cheung Hing.

A-Fu had also talked repeatedly about a “Mr Xu”, reportedly a well-connected Singaporean of Hong Kong origin operating out of Malaysia and said to be Cheng Pui Chee’s principle, albeit junior, business partner and long-term co-collaborator.

Because “Koh” is the Chinese Minnan dialect’s version of “Xu”, it became obvious that “Mr Xu” was likely to actually be “Mr Koh” – “Koh Seow Bean” – the father of Gary Koh of the Timberlux, Northwood and Wood & Wood network of companies, whom EIA had met in Singapore in 2013. Gary had alleged very corrupt inducements and payments of a similar nature to those alleged of Cheng Pui Chee.

Gary Koh

On the suspicion that Cheng’s partner Mr Xu was actually Mr Koh of the Timberlux network, EIA sought confirmation in the official records of numerous companies.

EIA acquired records for Thai Sawat Import Export Ltd in Thailand and the pieces of the puzzle finally fell into place.

The documents confirm that A-Fu’s “Shadow President” Cheng Pui Chee had changed his name in Thailand to Chetta Apipatana in the early 1960s and he and his father Soothie Apipatana (also spelt Suthee) and brother Marut Apipatana began working as directors in Thai Sawat; by 1975, they had taken control of the company.

Thai Sawat was one of only five Thai firms which maintained logging rights in Myanmar after the then-SLORC Government expelled all Thai logging companies earlier that year.

With the confirmation that Cheng Pui Chee is Chetta Apipatana, company documents clarify how, using his Thai name or the Thai names of his children and brother, Cheng Pui Chee registered shareholdings and/or directorships in a network of multiple Thai Sawat, Northwood and Timberlux companies to enable his teak empire to function across Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore and Thailand. Cheng retained his Chinese name in his Cheung Hing operations in Hong Kong.

A dead end?

Research confirmed that Cheng Pui Chee, aka Chetta Apipatana, appeared to be the “ghost kingpin” behind Myanmar’s teak trade, running his empire through a network of companies.

EIA then sought to meet the Shadow President himself and began planning a trip to Yangon. However, in May 2018 EIA learnt that the Shadow President had died suddenly the previous month.

Yangon Investigation

While Cheng’s death could have ended the investigation, EIA heard a huge stockpile of 100,000-200,000 tonnes of his corruptly acquired teak logs was being processed for export.

EIA wanted a meeting with Koh Seow Bean – Cheng Pui Chee’s principle business partner – and hoped to meet Cheng Pui Chee’s son Thanit Apipatana, said to be managing his father’s teak business after his death. EIA also hoped to meet a Myanmar citizen named Han Zaw Lin, suspected to be Cheng Pui Chee’s right-hand man in Myanmar.

In seeking meetings with Cheng Pui Chee’s people in Yangon, investigators were introduced to various industry operators who confirmed Cheng had been a major player. An MTE official, claiming to be a manager of timber export documentation, referred to Cheng’s operation in Myanmar as “CHC” (short for “Cheung Hing & Company”) which he said had been “the biggest company in Myanmar” in terms of teak log exports. A seasoned teak trader encountered in Yangon said Cheng Pui Chee hoarded teak had been known as “Myanmar’s second forest minister”.

On 31 October 2018, EIA finally secured a meeting with Han Zaw Lin, Cheng Pui Chee’s key lieutenant in Myanmar. He said that following Cheng Pui Chee’s death, the company was being run by himself as General Manager and by Koh Seow Bean in Malaysia and Singapore.

While Han Zaw Lin at no point bragged about Cheng Pui Chee’s bribery and teak grading fraud or the tens of millions of dollars in payments to offshore accounts of Government officials, he did confirm key aspects of the story EIA had learnt from A-Fu and information pertaining to Cheng Pui Chee’s role in supplying the EU market.

Han Zaw Lin

The following day, investigators finally met Koh Seow Bean (aka Mr Xu) of SCK/Timberlux/Northwood, Cheng Pui Chee’s principle business partner for international sales to Western markets and Gary Koh’s father.

Koh added to the multiple similar assertions regarding Cheng’s status, stating: “In teak business in the world, he is the biggest”, saying he and Cheng Pui Chee had used Timberlux and Cheng’s other companies as a means to be the largest teak suppliers in the world.

Koh Seow Bean

Koh Seow Bean claimed their operation had dominated not just in China but also in Western countries, saying “for over 10 years, even up to today, we are the biggest exporter to the US and European market.”

Lucrative luxury yacht manufacturers made up most of their Western customers, with Koh boasting: “As for the yacht industry, we’re the biggest exporter to the yacht companies in the world.”

The Shadow President - King of Burma Teak

In 2016, well-placed sources alluded to the existence of a teak kingpin, allegedly an untouchable and unknowable “ghost” behind Myanmar’s State-administered teak trade.

EIA’s sources suggested his name was “something like” PC Cheng, PC Chang or PC Chun, but could not identify him.

Then, in late 2017, EIA undercover investigators travelled to Taiwan – a centre of world-renowned teak saw millers – and the truth began to emerge.

EIA investigators met with Mr Zheng Kun Fu aka “A-Fu” of Kui Jay Corporation. He said he bought all his logs from a Hong Kong company called Xiangxin (Cheung Hing) said to be headed by a major player, whom he named as “Cheng Pui Chee.”

Cheng Pui Chee sounded exactly like the rumoured teak kingpin PC Cheng.

Cheng Pui Chee

A-Fu alleged that Cheng Pui Chee engaged in high-level corruption in collusion with senior Myanmar officials to defraud the state of timber revenues. Cheng’s corrupt acts allegedly included multi-million dollar bribes, and paying for the foreign education of the children of regime officials for a generation – all in exchange for preferential cut-price access to the best teak.

A-Fu

“ The Prime Minister in Yangon… the Chairman… the Fathers of the country would become jealous. Of the 60 million, 10 million would go straight into their pockets. They all have five houses… ”

A-Fu’s claims were corroborated in July 2018 by teak traders working at Yuli Wood, in mainland China, who were acquainted with Cheng Pui Chee, including Mr Zheng Tianren.

Cheng’s corruption reportedly went to the very top of Myanmar’s military administration. While Myanmar did not have a President during the period concerned, A-Fu can only have been referring to the de-facto leader of the country. During the period this corruption allegedly occurred (from the early 1990s to 2014), this can only have been Senior General Than Shwe, the head of the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) and (SPDC) Commander In Chief of the Myanmar Armed Forces from 1992 to 2011.

Through these completely illegal arrangements, Cheng became perhaps the world’s largest teak trader working within the official ‘legal’ system of trade administered by the MTE.

Zheng Tianren

“ He dared to gamble. Before, when the Burmese Government didn’t have money, they got it from him. First, they received 20 (million) then 40 (million)… then even when they wanted to buy an Air Force One they also asked him for money. ”

EIA sought to confirm “Cheng Pui Chee’s” full identity, and corroborate the story we had heard.

Cheng reportedly began his career under his father, importing teak into Hong Kong from Myanmar and Indonesia through his company Cheung Hing.

Publicly available sources about Cheung Hing give tantalising hints at connections between Cheng and influential timber cronies close to senior regime officials in Myanmar including Tay Za, who reportedly held shared in Cheng’s Hong Kong firm Cheung Hing.

A-Fu had also talked repeatedly about a “Mr Xu”, reportedly a well-connected Singaporean of Hong Kong origin operating out of Malaysia and said to be Cheng Pui Chee’s principle, albeit junior, business partner and long-term co-collaborator.

Because “Koh” is the Chinese Minnan dialect’s version of “Xu”, it became obvious that “Mr Xu” was likely to actually be “Mr Koh” – “Koh Seow Bean” – the father of Gary Koh of the Timberlux, Northwood and Wood & Wood network of companies, whom EIA had met in Singapore in 2013. Gary had alleged very corrupt inducements and payments of a similar nature to those alleged of Cheng Pui Chee.

Gary Koh

“ Never in my life did I think I would get to buy four zebras and two giraffes. ”

On the suspicion that Cheng’s partner Mr Xu was actually Mr Koh of the Timberlux network, EIA sought confirmation in the official records of numerous companies.

EIA acquired records for Thai Sawat Import Export Ltd in Thailand and the pieces of the puzzle finally fell into place.

The documents confirm that A-Fu’s “Shadow President” Cheng Pui Chee had changed his name in Thailand to Chetta Apipatana in the early 1960s and he and his father Soothie Apipatana (also spelt Suthee) and brother Marut Apipatana began working as directors in Thai Sawat; by 1975, they had taken control of the company.

Thai Sawat was one of only five Thai firms which maintained logging rights in Myanmar after the then-SLORC Government expelled all Thai logging companies earlier that year.

With the confirmation that Cheng Pui Chee is Chetta Apipatana, company documents clarify how, using his Thai name or the Thai names of his children and brother, Cheng Pui Chee registered shareholdings and/or directorships in a network of multiple Thai Sawat, Northwood and Timberlux companies to enable his teak empire to function across Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore and Thailand. Cheng retained his Chinese name in his Cheung Hing operations in Hong Kong.

A dead end?

Research confirmed that Cheng Pui Chee, aka Chetta Apipatana, appeared to be the “ghost kingpin” behind Myanmar’s teak trade, running his empire through a network of companies.

EIA then sought to meet the Shadow President himself and began planning a trip to Yangon. However, in May 2018 EIA learnt that the Shadow President had died suddenly the previous month.

Yangon Investigation

While Cheng’s death could have ended the investigation, EIA heard a huge stockpile of 100,000-200,000 tonnes of his corruptly acquired teak logs was being processed for export.

EIA wanted a meeting with Koh Seow Bean – Cheng Pui Chee’s principle business partner – and hoped to meet Cheng Pui Chee’s son Thanit Apipatana, said to be managing his father’s teak business after his death. EIA also hoped to meet a Myanmar citizen named Han Zaw Lin, suspected to be Cheng Pui Chee’s right-hand man in Myanmar.

In seeking meetings with Cheng Pui Chee’s people in Yangon, investigators were introduced to various industry operators who confirmed Cheng had been a major player. An MTE official, claiming to be a manager of timber export documentation, referred to Cheng’s operation in Myanmar as “CHC” (short for “Cheung Hing & Company”) which he said had been “the biggest company in Myanmar” in terms of teak log exports. A seasoned teak trader encountered in Yangon said Cheng Pui Chee hoarded teak had been known as “Myanmar’s second forest minister”.

On 31 October 2018, EIA finally secured a meeting with Han Zaw Lin, Cheng Pui Chee’s key lieutenant in Myanmar. He said that following Cheng Pui Chee’s death, the company was being run by himself as General Manager and by Koh Seow Bean in Malaysia and Singapore.

While Han Zaw Lin at no point bragged about Cheng Pui Chee’s bribery and teak grading fraud or the tens of millions of dollars in payments to offshore accounts of Government officials, he did confirm key aspects of the story EIA had learnt from A-Fu and information pertaining to Cheng Pui Chee’s role in supplying the EU market.

Han Zaw Lin

EIA: “Government to government, you must have good contact right?”

HZL: “Sure!” (nods and laughs)

The following day, investigators finally met Koh Seow Bean (aka Mr Xu) of SCK/Timberlux/Northwood, Cheng Pui Chee’s principle business partner for international sales to Western markets and Gary Koh’s father.

Koh added to the multiple similar assertions regarding Cheng’s status, stating: “In teak business in the world, he is the biggest”, saying he and Cheng Pui Chee had used Timberlux and Cheng’s other companies as a means to be the largest teak suppliers in the world.

Koh Seow Bean

“ Mr Cheng and I are very low profile here, even among the locals, and very, very few people know who we are. ”

Koh Seow Bean claimed their operation had dominated not just in China but also in Western countries, saying “for over 10 years, even up to today, we are the biggest exporter to the US and European market.”

Lucrative luxury yacht manufacturers made up most of their Western customers, with Koh boasting: “As for the yacht industry, we’re the biggest exporter to the yacht companies in the world.”

Cheng’s Western Markets

The US

East Teak Fine Hardwoods (ETFH) is the US’s biggest Myanmar teak importer and buys from multiple companies in the Shadow President’s network.

Trade records confirm at least 151 shipments from Kui Jay Corporation during the past decade, including four in 2018, making A-Fu ETFH’s second biggest supplier worldwide. Timberlux Sdn Bhd is ETFH’s next biggest supplier, sending 143 shipments over the same period.

Timberlux Sdn Bhd also sent 17 shipments to J Gibson McIlvain (the second biggest US importer of Myanmar teak) and 13 to TeakDecking Systems (TDS), the biggest pre-fabricated yacht decking manufacturer in the world.

All of Cheng Pui Chee’s wood is understood to violate of the US Lacey Act.

Cheng’s Western Markets

The US

East Teak Fine Hardwoods (ETFH) is the US’s biggest Myanmar teak importer and buys from multiple companies in the Shadow President’s network.

Trade records confirm at least 151 shipments from Kui Jay Corporation during the past decade, including four in 2018, making A-Fu ETFH’s second biggest supplier worldwide. Timberlux Sdn Bhd is ETFH’s next biggest supplier, sending 143 shipments over the same period.

Timberlux Sdn Bhd also sent 17 shipments to J Gibson McIlvain (the second biggest US importer of Myanmar teak) and 13 to TeakDecking Systems (TDS), the biggest pre-fabricated yacht decking manufacturer in the world.

All of Cheng Pui Chee’s wood is understood to violate of the US Lacey Act.

Europe

Alfred Neumann GmbH is a major German supplier of Myanmar teak to the EU yacht industry and recently supplied the wood to the flagship German Navy training vessel the Gorch Fock. A-Fu produced the business card of Alfred Neumann’s principle teak buyer, Peter Eick. He said Peter Eick had purchased “a few thousand tonnes” of teak logs directly from Cheng Pui Chee in 2013, making a lot of money in the process.

A-Fu also mentioned an Italian buyer called Luca Rossi from Trieste, Italy. Luca Rossi and family members have run various companies importing Myanmar teak into Europe from Cheng-linked operators for many years, including Antonini Legnami and Adriatic Timber. Since 2015, Luca Rossi has run Timberlux Srl, established as the Agent or “trustee” of Timberlux Sdn Bhd in Malaysia – Cheng Pui Chee’s and Koh Seow Bean’s principle conduit to the international market.

All of this trade violates the EUTR.

Europe

Alfred Neumann GmbH is a major German supplier of Myanmar teak to the EU yacht industry and recently supplied the wood to the flagship German Navy training vessel the Gorch Fock. A-Fu produced the business card of Alfred Neumann’s principle teak buyer, Peter Eick. He said Peter Eick had purchased “a few thousand tonnes” of teak logs directly from Cheng Pui Chee in 2013, making a lot of money in the process.

A-Fu also mentioned an Italian buyer called Luca Rossi from Trieste, Italy. Luca Rossi and family members have run various companies importing Myanmar teak into Europe from Cheng-linked operators for many years, including Antonini Legnami and Adriatic Timber. Since 2015, Luca Rossi has run Timberlux Srl, established as the Agent or “trustee” of Timberlux Sdn Bhd in Malaysia – Cheng Pui Chee’s and Koh Seow Bean’s principle conduit to the international market.

All of this trade violates the EUTR.

Ongoing smuggling into China

Myanmar’s regulations require all timber exports to occur through Yangon seaports, Yet massive timber smuggling across the border between Kachin State and China’s Yunnan province has been documented for decades.

An intricate web of criminal syndicates has conspired with ethnic armed groups and elements of the Myanmar military to traffic valuable timber such as teak to China, with bribes being levied at multiple checkpoints by all actors along the route.

The criminal profits are huge. In 2013 Chinese customs recorded imports of 938,000 m3 of logs worth half-a-billion dollars from Myanmar, with 94 per cent transported overland.

Despite a clamp-down in 2015, by late 2016 logs and sawn timber were once again flowing to China, albeit at reduced rates, but with trade now largely focussed on teak, due to increased demand for the luxury wood in China.

In June 2018, EIA investigators witnessed more than 200 trucks in one border crossing area laden with teak timber and waiting to cross into Nongdao in Yunnan. EIA undercover investigators also spent several days with Yi Fuxiang, owner of Yingjiang Neisheng Timber, a major teak smuggler who largely supplies to China’s domestic market.

Yi told EIA he consolidated teak at his sawmill in an area of Kachin State controlled by an ethnic armed group, but that the wood was illegally logged in Myanmar-government controlled forests in neighbouring Shan State. The illegal teak is transported to Kachin by 300 motorbike drivers, and then trucked to the border, with bribes being paid to ethnic armed groups and both Myanmar and Chinese officials manning checkpoints along the route.

In the same month EIA investigators travelled to Dongguan in Guangdong Province, and met with representatives of Yuli Wood Industry, which specialises in teak. Yuli’s staff told EIA that since Myanmar’s April 2014 log export ban all their teak was from the Kachin-Yunnan border, saying “all of it is illegally logged. All of it. 101%”.

Asked how they get the wood out of Myanmar into China, Yuli staff said “most importantly, it’s still having to… bribe… bribe… bribe… So, if it’s one particular customs post, then we’ll just buy it up.”

Ongoing smuggling into China

Myanmar’s regulations require all timber exports to occur through Yangon seaports, Yet massive timber smuggling across the border between Kachin State and China’s Yunnan province has been documented for decades.

An intricate web of criminal syndicates has conspired with ethnic armed groups and elements of the Myanmar military to traffic valuable timber such as teak to China, with bribes being levied at multiple checkpoints by all actors along the route.

The criminal profits are huge. In 2013 Chinese customs recorded imports of 938,000 m3 of logs worth half-a-billion dollars from Myanmar, with 94 per cent transported overland.

Despite a clamp-down in 2015, by late 2016 logs and sawn timber were once again flowing to China, albeit at reduced rates, but with trade now largely focussed on teak, due to increased demand for the luxury wood in China.

In June 2018, EIA investigators witnessed more than 200 trucks in one border crossing area laden with teak timber and waiting to cross into Nongdao in Yunnan. EIA undercover investigators also spent several days with Yi Fuxiang, owner of Yingjiang Neisheng Timber, a major teak smuggler who largely supplies to China’s domestic market.

Yi told EIA he consolidated teak at his sawmill in an area of Kachin State controlled by an ethnic armed group, but that the wood was illegally logged in Myanmar-government controlled forests in neighbouring Shan State. The illegal teak is transported to Kachin by 300 motorbike drivers, and then trucked to the border, with bribes being paid to ethnic armed groups and both Myanmar and Chinese officials manning checkpoints along the route.

In the same month EIA investigators travelled to Dongguan in Guangdong Province, and met with representatives of Yuli Wood Industry, which specialises in teak. Yuli’s staff told EIA that since Myanmar’s April 2014 log export ban all their teak was from the Kachin-Yunnan border, saying “all of it is illegally logged. All of it. 101%”.

Asked how they get the wood out of Myanmar into China, Yuli staff said “most importantly, it’s still having to… bribe… bribe… bribe… So, if it’s one particular customs post, then we’ll just buy it up.”

Stemming the tide

The theft of Myanmar’s teak stocks – whether by Myanmar’s military rulers and henchmen such as Cheng Pui Chee or by armed ethnic groups and predatory cross-border timber smugglers such as Yi Fuxiang and Yuli Wood has been conducted with impunity for too long.

Domestic Protections

China’s complicity

EU Timber Regulation

The US Lacey Act

(Click images for details)

Stemming the tide

The theft of Myanmar’s teak stocks – whether by Myanmar’s military rulers and henchmen such as Cheng Pui Chee or by armed ethnic groups and predatory cross-border timber smugglers such as Yi Fuxiang and Yuli Wood has been conducted with impunity for too long.

Domestic Protections

China’s complicity

EU Timber Regulation

The US Lacey Act

(Click images for details)

Recommendations

The Government of Myanmar should

• Investigate and prosecute high level corruption in the timber trade in Myanmar, including by military and Government officials as well as private sector actors

• Reduce logging operations countrywide pending a full assessment of current forest conditions that include indigenous communities and people reliant on Myanmar’s forests

• Develop a mechanism for inclusive dialogue in conflict areas that includes natural resources

• In the absence of real reform, abolish the role of the Myanmar Timber Enterprise in implementing logging and timber trade and establish a new multistakeholder management body that delivers greater transparency and accountability for all stakeholders

• Build on the current multistakeholder process, including representatives from forestbased communities, to continue preparing Myanmar for possible Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade (FLEGT) discussions with the European Union

• Ensure that all existing and future bilateral agreements with foreign governments on illegal logging, illegal timber trade and forestry investment such as Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) are made public

• Establish a task force that includes inter-agency cooperation to address cross-border smuggling and illicit timber trade through Yangon port.

Recommendations

The Government of Myanmar should

- Investigate and prosecute highlevel corruption in the timber trade in Myanmar, including by military and Government officials as well as private sector actors

- Reduce logging operations countrywide pending a full assessment of current forest conditions that include indigenous communities and people reliant on Myanmar’s forests

- Develop a mechanism for inclusive dialogue in conflict areas that includes natural resources

- In the absence of real reform, abolish the role of the Myanmar Timber Enterprise in implementing logging and timber trade and establish a new multistakeholder management body that delivers greater transparency and accountability for all stakeholders

- Build on the current multistakeholder process, including representatives from forestbased communities, to continue preparing Myanmar for possible Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade (FLEGT) discussions with the European Union

- Ensure that all existing and future bilateral agreements with foreign governments on illegal logging, illegal timber trade and forestry investment such as Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) are made public

- Establish a task force that includes inter-agency cooperation to address cross-border smuggling and illicit timber trade through Yangon port.

The international community should

• Support mechanisms in Myanmar providing for inclusive dialogue on natural resources in conflict areas

• Support the improvement of forest and natural resource governance within ethnic administrations and ethnic civil society’s ability to manage and protect forests

• Encourage laws prohibiting imports of illegal timber where currently absent (e.g. China, India and Thailand) and make resources available to implement and enforce existing laws on illegal timber trade (e.g. Australia, the EU and US).

The international community should

- Support mechanisms in Myanmar providing for inclusive dialogue on natural resources in conflict areas

- Support the improvement of forest and natural resource governance within ethnic administrations and ethnic civil society’s ability to manage and protect forests

- Encourage laws prohibiting imports of illegal timber where currently absent (e.g. China, India and Thailand) and make resources available to implement and enforce existing laws on illegal timber trade (e.g. Australia, the EU and US).

China should

• Support and respect Myanmar’s log export ban by putting in place reciprocal measures in China

• Institute a clear legal prohibition on all imports of illegally sourced timber

• Eliminate the role of state-owned enterprises in procuring imports of illegal timber in China

• Place responsibility for eradicating China’s illegal timber trade in the hands of a formal coordinating body headed by senior officials from the Commerce and Foreign Ministries

• Ensure that any bilateral agreements on illegal logging, such as MOUs, are made public.

China should

- Support and respect Myanmar’s log export ban by putting in place reciprocal measures in China

- Institute a clear legal prohibition on all imports of illegally sourced timber

- Eliminate the role of state-owned enterprises in procuring imports of illegal timber in China

- Place responsibility for eradicating China’s illegal timber trade in the hands of a formal coordinating body headed by senior officials from the Commerce and Foreign Ministries

- Ensure that any bilateral agreements on illegal logging, such as MOUs, are made public.

State of Corruption

Download the full report, detailing the results of our investigations. This includes references and picture credits.

ျမန္မာဘာသာျဖင့္လည္း ရယူႏိုင္ပါသည္။ (Burmese translation available) »

State of Corruption

Download the full report, detailing the results of our investigations. This includes references and picture credits.

ျမန္မာဘာသာျဖင့္လည္း ရယူႏိုင္ပါသည္။ (Burmese translation available) »